Paul Zak spent over two decades developing the science beneath his company, Immersion. His tastemaker software aims to measure and predict how people respond to music, movies and other experiences by tracking their brain activity through a smartwatch or fitness tracker.

With a newly launched software-as-a-service platform, his mind-reading tool is now available to the masses for as little as $199 a month.

But the wide release of a technology that purports to know people better than they know themselves is worrying to some, who say it could limit artistic expression, perpetuate unconscious biases and, in the wrong hands, subject unwilling people to spying and manipulation.

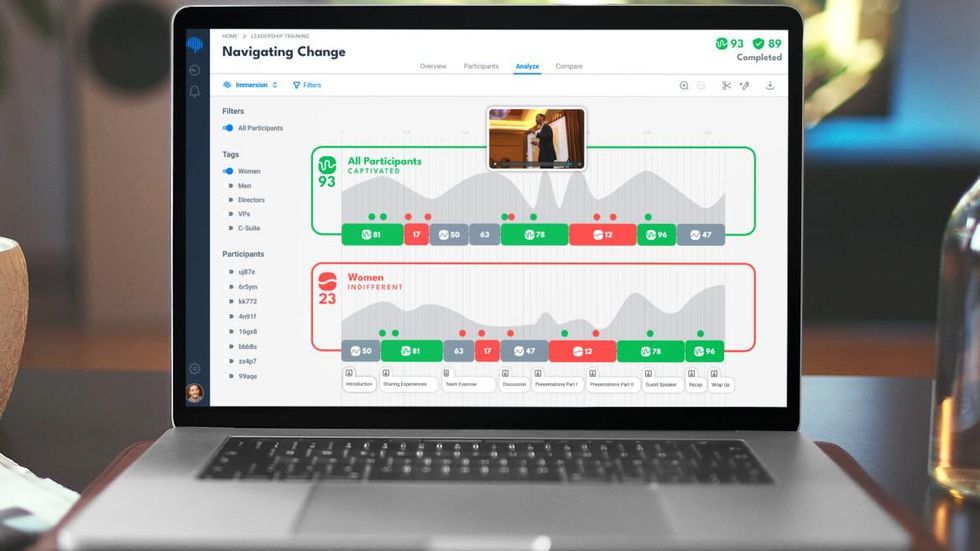

Zak’s tool measures emotional resonance, or what he calls “immersion.” It uses sensors to track attention levels and infer brain levels of oxytocin, the so-called “love hormone” known for its association with bonding that works as a neurotransmitter. The sensors monitor how a person’s brain responds to a given stimulus, moment by moment. Software generates a readout that provides real-time feedback potentially useful for everything from testing Hollywood audiences to understanding what resonates during a work presentation.

Through sensors Immersion measures someone’s pulse, which Zak says is correlated with attention levels.

“Attention is the necessary condition; immersion is the sufficient condition,” he added, noting that the latter is measured by oxytocin: a naturally occurring chemical in the brain that, he says, “is why people cry at movies when the boy kisses the girl.”

Paul Zak directs Claremont Graduate University’s Center for Neuroeconomic Studies

Zak, who directs Claremont Graduate University’s Center for Neuroeconomic Studies, researches how brain activity corresponds to decision-making. His papers have been cited by academic publications over 15,000 times. He is not without his critics, though, some of whom have argued that oxytocin, in addition to correlating with feelings like empathy and trust, can also correlate with envy and tribalism.

As wearable sensors improved over time, Zak says he became able to map the data gathered by noninvasive, everyday items like smartwatches back to the brain-activity readouts he’s gathered for years in his lab from blood-draws and expensive medical equipment.

“We created the first democratized platform for neuroscience where anybody could measure what the brain loves in real time,” he said. And with this week’s release of his company’s SaaS platform, just about anyone can use it.

After three years working in stealth, Immersion ramped up its marketing right around the onset of the pandemic. The company began as a service focused primarily on helping entertainment companies create better content.

It has worked with a handful of Hollywood studios, including Paramount and Warner Bros, to help produce movie trailers, determine slates for the upcoming fall TV lineup and ascertain whether during lockdown people preferred to watch new or familiar content.

Zak said Immersion can predict hits with over 80% accuracy. Music streamer Pandora has used the service to study which songs listeners would enjoy, he said.

The idea of using mind-interpreting software on the masses to shape what we experience offers intriguing possibilities, but some say it could also amplify biases and distort creative output by favoring content that scores well on brain-activity metrics.

Traditional focus groups rely on surveys to gather feedback. When people fill out questionnaires on what they liked and disliked about a given experience, they have time to counteract their subconscious biases that may instinctively cause them to recoil from certain concepts they find unappealing, such as homosexuality, said Patrick Lin, director of Ethics + Emerging Sciences Group at Cal Poly in San Luis Obispo. Relying on real-time brain activity, though, doesn’t give people the opportunity to self-correct for those biases.

“You can hide that in a survey, but you might not be able to hide it from a technology like this,” said Lin. That could skew productions away from edgier or more provocative fare that Lin says can be useful for dislodging society from its comfort zones.

But to Zak, being able to measure how people really feel offers tremendous potential for improving and even lengthening lives. He is in talks with smartwatch makers to include Immersion on their devices out of the box. The reason someone would want that, he said, is to learn from their data what frustrates them and what makes them happy.

“Then you can begin to curate people’s lives for greater happiness,” he said. “And we know that individuals who are happier live longer.”

When the world went remote, film production slowed down and face-to-face contact dwindled, and other kinds of businesses began looking to Immersion for help. Companies needed ways to monitor the effectiveness of their attempts to adapt to a distributed world where social cues like body language were no longer available and surveys were unreliable. Zak said he has signed on three of the five FAANG companies as clients to help them make meetings and employee trainings more engaging.

Immersion is designed so that, in these situations, employers can only match data to specific employees if they have consented to having their identities revealed. Zak said Immersion does not store any personally identifiable information online, and noted that his company has worked with European firms and was deemed compliant with the EU’s strict data privacy-protection laws.

But going deeper into workers’ minds not only raises privacy questions but could also make employees’ lives more difficult.

One could easily imagine unscrupulous companies using the technology to squeeze out every last drop of employee productivity, said Michael Karanicolas, executive director of the UCLA Institute for Technology, Law and Policy. He pointed to news reports of Amazon employees struggling to find time to use the bathroom during their shifts as an example of the danger.

When asked about potential ethical concerns, Zak emphasized his company’s policy of requiring consent before people’s brain activity is tracked.

Zak has been a trailblazer in the field of neuroeconomics. He has received grants totaling over $1 million from the U.S. Department of Defense and Intelligence community to research what motivates people to make decisions and take action. His 2011 TED talk on oxytocin has nearly 2 million views. He was even once named one of the 10 sexiest geeks by WIRED Magazine.

Zak formed Immersion when the university where his lab is based grew uncomfortable with commercial applications of his research, he said.

In March this year, his company landed a $1.7 million seed investment led by Silicon Valley billionaire investor Tim Draper.

“The real arc of my professional life has been to create technologies to help people live more fulfilled and happier lives,” he said. “And so this is really the culmination for me of 25 years of my life.”

Yet with his company’s lofty goals comes the possibility, as with any technology, of unintended consequences.

“These mindreading technologies are going to chip away at the last fig leaf we have,” said Lin, “–the privacy inside our own head.”

Editor’s note: This story was updated to clarify role of oxytocin

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web

/assets/images/provider/photos/2672875.jpg)

More Stories

10 Ways Your Brain Changes Drastically As You Age • Wellness Captain

8 Ways to Rock Your Holiday Leftovers

Difference Between Kidney Stone and Gallstone